Julie R. Ashwill, B.A.

Springwell, Inc.

Waltham, MA

Introduction

On average, men earn higher wages than women in the United States, across and within occupations (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014). In 2012, women earned $0.81 for every dollar earned by men (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014). There are several explanations for the “gender wage gap”. Petersen and Morgan (1995) propose three possibilities:

- “Allocative discrimination” whereby women are allocated to occupations and industries that pay lower wages on average, often during the hiring process and reified in the promotion process

- “Valuative discrimination” whereby female-dominated industries pay less than male-dominated industries

- “Within-job wage discrimination” whereby women make less than men within the same occupation

The first two explanations acknowledge that women and men are often segregated by occupation and industry. Despite general increases in gender equality over the past several decades, occupational segregation by gender remains an issue (McGrew, 2016). Why does occupational segregation continue?

In this report, I pose the following two questions: (1) is the use of labor market information (LMI) associated with increased gender normative job placements? (2) Does geographic region play a role in the likelihood of gender normative job placement? I hypothesize that state VR agencies (SVRAs) that do not report using traditional or real-time LMI to assist consumers obtain employment are less likely to close them in gender normative jobs. LMI provides information about wage and employment trends within specific industries (ExploreVR, 2016). Ideally, VR counselors use LMI to assist job seekers to make informed choices about their career goals. Without LMI, job seekers may be more likely to consider occupations consistent with stereotypes about their gender, age, disability or other demographic characteristics.

I also predict that states in the Southern region of the U.S. are more likely to close clients into jobs that conform to traditional gender roles. This prediction is based on Gallup Poll data of political ideology in the United States. Individuals from states in the Southern U.S. are more likely to report “conservative” political ideology than individuals from other regions (Saad, 2009). Conservative political ideology is associated with support for stronger societal gender norms (Wallach Scott, 1999).

Method

In order to test these hypotheses, I downloaded two datasets from the ExploreVR Data Lab:

- 2014 Vocational Rehabilitation (VR) Business Relations Across States

- RSA 911: VR Client Occupations by State and Territory 2008-2012

I also examined data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), Median Weekly Earnings of Full-time Wage and Salary Workers by Detailed Occupation and Sex (2015).

To define “gender normative jobs”, I chose six Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) codes from the RSA-911 data. I selected three occupations where more than 70% of the closed clients identified as female and three occupations where more than 70% of the closed clients identified as male. I matched these SOC codes with the 2015 BLS data to determine the average weekly earnings in these occupations by gender in 2015, and to confirm that these occupations were occupationally segregated by gender in non-VR consumer populations. I chose SOC codes for gender normative occupations that were generally matched by major SOC and skill level, and for which adequate data was available in the RSA-911 dataset. For female-dominated occupations, I examined Childcare, Housekeeping, and Nursing Aides. For male-dominated occupations, I examined Janitors, Security Guards, and Freight and Stock Laborers. Housekeeping and Janitors are both Building and Grounds Cleaning and Maintenance Occupations (BLS, 2015). Nursing Aides and Security Guards are both Service Occupations (BLS, 2015). Childcare is also a Service Occupation, and Laborers and Freight, Stock, and Material Movers is a Production, Transportation, and Material Moving occupation (BLS, 2015).

In order to test the effect of VR agencies’ LMI use on their clients’ gender-normative outcomes, I examined responses to variables in the dataset, 2014 Vocational Rehabilitation (VR) Business Relations Across States and its corresponding Codebook on the ExploreVR Data Lab: D1 (“Does your agency use Labor Market Information?”); D4 (How does your VR agency use traditional labor market data?”); D5 (“Does your VR agency use real-time labor market data?”); and D8 (“How does your VR agency use real-time labor market data?”). I then calculated a “gender normativity score” by sorting the agencies in the RSA 911: VR Client Occupations by State and Territory 2008-2012 dataset into the six gender normative SOC codes to determine the percentage of males and females from each responding SVRA for each occupation. I only examined agencies that also responded to the 2014 Vocational Rehabilitation (VR) Business Relations survey. I averaged the percentages from each occupation category across the six occupations. Agencies where more than 70% of the closed clients in Childcare, Housekeeping, and Nursing Aides were female were considered gender normative. Similarly, agencies where more than 70% of the closed clients in Security, Janitorial, and Laborers and Freight, Stock, and Material Movers were male were considered gender normative. Finally, I ran a series of independent samples t-tests that compared agencies that responded “yes” vs. “no” to each of the questions, with gender normativity score as the dependent variable.

To address the second question motivating this research, I separated state agencies that responded to questions D1, D4, D5, and D8 on the Business Relations survey into regional categories according to the U.S. Census Bureau classification (West, Midwest, Northeast, and South). I then ran a one-way analysis of variance to compare the gender normativity scores in each of these regions.

Results

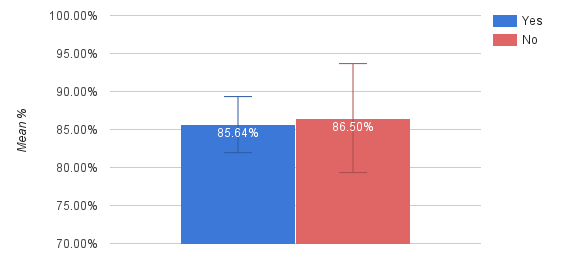

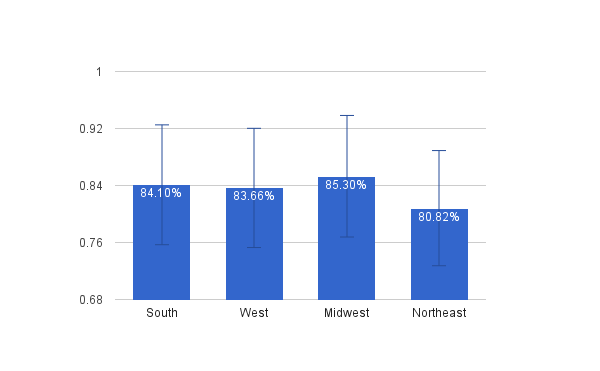

I hypothesized that agencies that do not report using traditional or real-time LMI to assist consumers obtain employment are less likely to close them in gender normative jobs. In fact, agencies’ reported use of LMI did not impact gender normative occupation closures. There is no statistically significant relationship between agencies’ use of traditional or real-time LMI (see Figure 1) to assist consumers in making an informed choice about their vocational goal or to inform job placement and gender normative job placement. VR agencies that did not use any type of LMI were not more likely to place consumers in gender normative occupations. Further, there were no statistically significant regional differences in gender normative occupation closures (see Figure 2).

Of the 67 VR agencies that responded to D1, “Does your agency use Labor Market Information?”, 61 answered “Yes”, and 4 answered, “No”. LMI use did not influence gender normativity score, t(62) = -0.33, p < 0.05. Of the 59 agencies that responded to question D4 “How does your VR agency use traditional labor market data?” 56 responded that they use traditional LMI to “assist consumers in making an informed choice about their vocational goal”. This also had no effect on the gender normativity of clients’ placements, t(56) = -0.25, p < 0.05). 51 agencies (of the 59 agencies that responded to question D4) reported using LMI “to inform job placement”. There were also no differences between agencies who answered affirmatively to this question and those who did not, t(56) = -0.22, p < 0.05. In all, 3 VR agencies do not use traditional LMI to assist consumers in making an informed choice about their vocational goal, and 8 VR agencies do not use traditional LMI to inform job placement.

58 SVRAs responded to question D5, “Does your VR agency use real-time labor market data?” 15 SVRAs responded “Yes” and 43 SVRAs responded, “No” (see Table 1). There were no differences in gender normativity scores based on the response to question D5, t(55) = 0.37, p < 0.05. Of the 15 who responded positively to using real-time LMI, all 15 SVRAs responded to the question D8, “How does your VR agency use real-time labor market data?” with the response, “To assist consumers in making an informed choice about their vocational goal”. Additionally, 13 of the 15 SVRAs reported that they use real-time LMI to “inform job placement”. Two SVRAs who use real-time LMI do not use it to inform job placement. Again, there were no differences in gender normativity scores based on the response to this question, t(12) = 0.15, p < 0.05.

Table 2 shows the gender normativity score for each U.S. region. I hypothesized that states in the Southern region of the U.S. would more likely close clients into jobs that conform to traditional gender roles. Contrary to my second hypothesis, the Midwest region had the highest rates of gender normative closures (85.1%), however the differences between regions were not statistically significant, F(3, 61) = 0.65, p < 0.05. There was additionally no relationship between real-time LMI use and gender normative job occupation closures by region (i.e., an interaction between region and response to question D5, F(3, 48) = 0.45, p < 0.05.

Discussion

Although over 70% of Childcare, Housekeeping, and Nursing Aide closures were female and over 70% of Janitor, Security, and Freight closures were male in the nearly all of the SVRAs that participated in the 2014 survey, this was not associated significantly with the agencies’ use of LMI. However, this finding alone is worth further study. Across all SVRAs in all four major regions in the U.S., occupational segregation is prevalent. Further research could compare occupations that require a higher level of education to determine if the gender normative ratios are as high as jobs that require less education. Additionally, examining age and other demographics could provide additional explanation for the high prevalence of gender normative occupation closures.

Most SVRAs report using LMI. Future inquiry should determine how VR staff use LMI to assist clients with making informed choice and with job placement. One limitation of this analysis is that the occupations dataset was from 2008-2012, but the business relations survey data was from 2014. It is possible that fewer agencies were using LMI during the 2008-2012 timeframe. It would also be important to know the sources of LMI VR is accessing, and consumers’ understanding of the LMI they receive. Further understanding the sources and implications of LMI could help explain reasons for occupation closures in gender normative and non-gender normative careers.

Figure 1. Gender Normativity Score (mean +/- standard error) and Responses to Question D5 (Does your VR agency use real-time labor market data?)

|

D5: Does your VR agency use real-time labor market data (LMI)? |

N |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

|

“No” |

43 |

86.50% |

8.29% |

|

“Yes” |

14 |

85.64% |

4.31% |

Figure 2. Regional Differences in Gender Normativity Scores (mean +/- standard error)

|

Region |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

N |

|

|

South |

84.10% |

4.93% |

23 |

|

|

West |

83.66% |

14.15% |

13 |

|

|

Midwest |

85.30% |

3.71% |

17 |

|

|

Northeast |

80.82% |

11.54% |

12 |

|

|

Total |

83.72% |

8.63% |

65 |

|

References

ExploreVR (2016). 2014 Vocational Rehabilitation (VR) Business Relations Across States [Data file]. Retrieved from: http://www.explorevr.org

ExploreVR (2016) Labor market information (LMI) toolkit. Retrieved from: http://www.explorevr.org

ExploreVR (2016). VR Client Occupations by State and Territory from 2008-2012. [Data file]. Retrieved from: http://www.explorevr.org

McGrew, W. (2016). Gender segregation at work: “separate but equal” or “inefficient and unfair”. Retrieved from http://equitablegrowth.org/human-capital/gender-segregation-at- work-separate-but-equal-or-inequitable-and-inefficient/

Petersen, T., & Morgan, L. A. (1995). Separate and unequal: Occupation-establishment sex segregation and the gender wage gap. American Journal of Sociology, 101, 329–365.

Saad, L. (2009). Political Ideology: "Conservative" Label Prevails in the South. Retrieved from: http://www.gallup.com/poll/122333/Political-Ideology-Conservative-Label-Prevails- South.aspx

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2015) Median weekly earnings of full-time wage and salary workers by detailed occupation and sex. Retrieved from: http://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat39.pdf

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Reports (2014). Women in the labor force: A databook. Retrieved from: http://www.bls.gov/cps/wlf-databook-2013.pdf

U.S. Census Bureau (2016) Census Regions and Divisions of the United States.

Retrieved from http://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps- data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf

Wallach Scott, J. (1999). Gender and the Politics of History. New York: Columbia University Press.

ExploreVR staff do not take responsibility for the opinions discussed in this analysis.